From Medium: Deconfusing Pre- and Post-processing

This post was originally published on Medium in 2015. I decided to carry it over to my blog to keep it safe

If you read my last article on PostCSS, I hope that you don’t get the feeling that I don’t like that tool. Quite on the contrary! I love it. I use it on a daily basis for all my projects.

But sometimes, I’m confused about certain expectations by developers. Especially when it comes to tools and revolutionary concepts they bring along. Quite often I’ve seen comments like this in my Twitter timeline or on several blog posts all around the web:

Are you still pre-processing or do you already post-process? It’s 2015 after all!

The term Post-processing is a huge thing right now. The revelation for all people bound by monolithic do-it-alls. A return to simplicity and smaller toolchains. And even more! Writing clean and standards-based CSS to convert it to something browser’s can digest? That does sound tempting. Write the CSS of the future. When the future’s there, forget about your tools but continue to write the same style of code.

Those are good ideas, and tools like PostCSS are exceptionally well executed. And for a lot of people PostCSS is synonymous with post-processors. However, some things always seemed a little funny to me. It wasn’t until recently that I could put my finger on it. The trigger was a tweet by Hugo:

It’s not post-processing if it happens before hitting the browser. @prefixfree is a post-processing tool. @PostCSS — @hugogiraudel

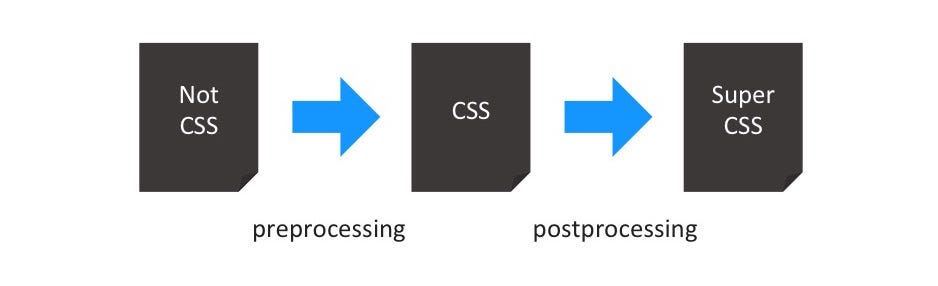

Huh? Rad thoughts. I always thought I could easily distinguish between the pre- and post-processing tools. One takes a language that compiles to CSS. And the other one aligns and refurbishes CSS to have the best possible outcome for today’s browsers. But Hugo’s thoughts were absolutely valid. There is still a point in time where CSS can further be processed: In the browser. So when does pre-processing stop and post-processing start?

This led me to the conclusion of the problem that was itching my brain: I just don’t like the term post-processor. And if I think about it, I don’t like preprocessing either.

A look back: Pre-processing and post-processing pre-postcss-craze #

So let’s see how the terms were understood by me before the dawn of PostCSS. Maybe a lot of other developer’s thought so too.

Pre-processing always involved another language. Sass, LESS, Stylus. You name it. The language’s name was also the name of the tool. And you wrote in that language to process it to CSS. This coined the term pre-processor: First it’s something different, then it’s CSS.

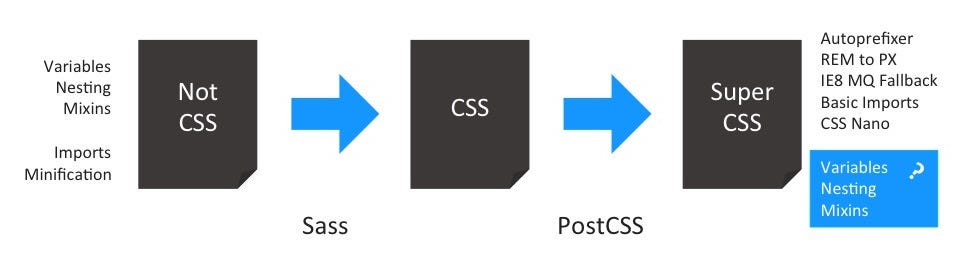

Post-processing on the other hand happened after we already had CSS in place. We used post-processors to tweak it and improve it. To get more out of our CSS than we could do by ourselves. You ask which improvements I am talking about? It’s getting clearer once you look at figure 2:

Post-processors did the heavy lifting for us. They made changes to our code, which we didn’t want to care about: Applying vendor prefixes automatically. Creating pixel fallbacks for every “rem” unit that we used. And extracting all the mobile first media query content for a certain viewport to give IE8 something nice to present.

Pre-processors were used for all the things CSS couldn’t do. Things that required our craft. Variables, Mixins, Nesting. You know the deal. Good extensions that made our life easier. And a tad crazier. Plus, we got some built-in performance improvements! Sass combined all our files to one minified CSS output.

You heard now two main concepts on both sides. Pre-processing was all about crafting and things that CSS couldn’t do (extensions). Post-processing was about optimisations and automation.

The “new” world with PostCSS #

How does the world look like now that we’ve a dedicated tool for post-processing? Suddenly we can do so much more on the right side of our toolchain. The same tool we use for Autoprefixer, fallbacks and other optimisations can help with all the crafting.

But is this still post-processing, you might ask? Sort of. At least variables and nesting do have working drafts at the W3C. The first one is even fully implemented in Firefox. The idea of having those features in PostCSS is to provide the same concept as the “rem to px” converter did. If it’s available in the browser, you can use it. Otherwise, we provide the necessary fallback. And for the sake of convenience, start with the fallback until you can drop the tool.

Other features however are not based upon standards or working drafts. Mixins won’t happen any time soon. Other extensions in the PostCSS ecosystem are also far away from becoming a recommendation, let alone a working draft.

So, is it even appropriate calling it “post-processing” anymore?

New terms for the tasks: Authoring and Optimisation #

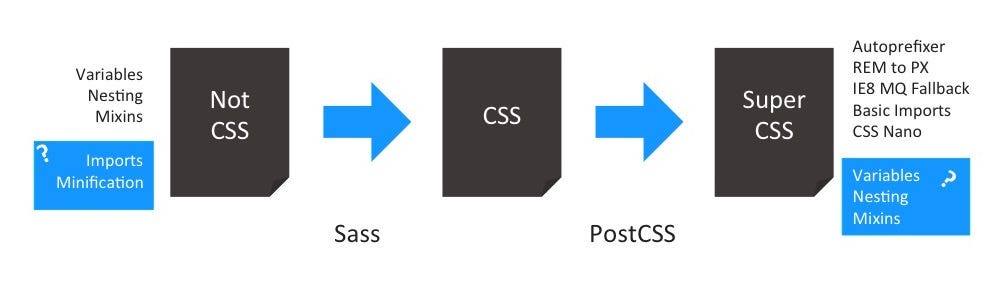

If you take it seriously, the use of CSS variables — even with it being backed by the spec — is pre-processing. None of the code that you write is going to end up in the browser. So how do they differ from the simple variables Sass has to offer? Other than having a fancier syntax, they don’t. I think this was Hugo’s original point.

This doesn’t make CSS variables less useful. They still help us with the same things as Sass variables did. But also on the same level: When we are authoring our code. Same goes for CSS nesting. Or basically any other future syntax or CSS extension PostCSS module. They will not end up in the browser, but they allow us write better code.

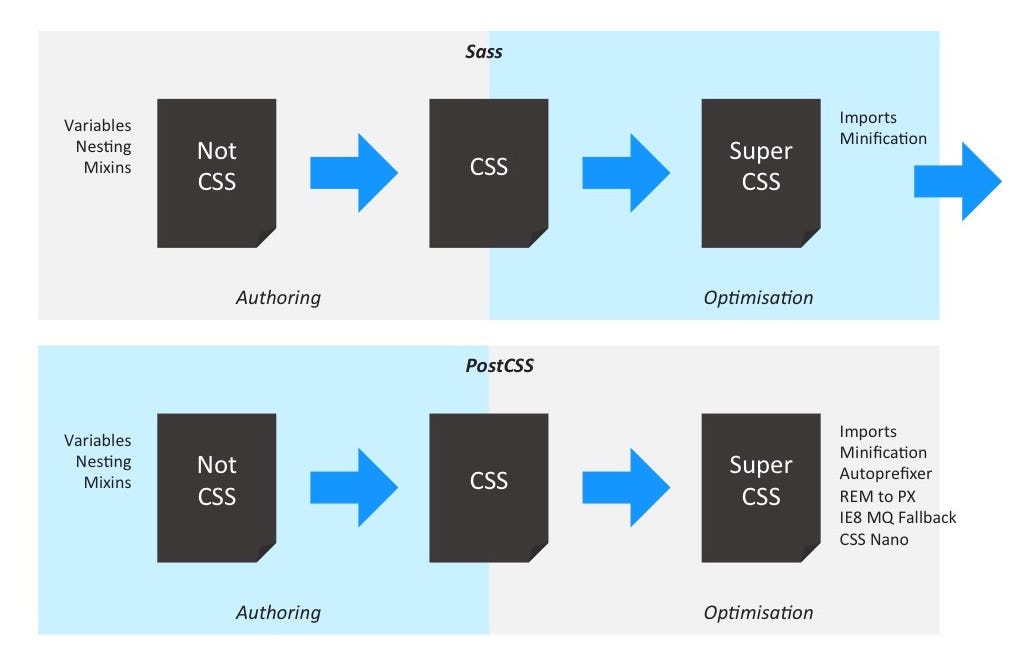

Likewise, we can also split up the features pre-processors like Sass or LESS have to offer. But this time we split away the optimisations from the far more obvious authoring features, as seen in figure 4.

Automatic imports and minification have always been nice add-ons. Features that originated from other tools and found their way into the pre-processing chain. Even though they were optimisations done on compiled CSS code. Post-processing tasks done in a pre-processor.

With this new insights, the original toolchain does not fit anymore. PostCSS is not only post-processing. And Sass is not only pre-processing. One could even say that PostCSS is their most favourite pre-processor. And another one loves Sass as a post-processor.

Non Identical Twins #

I think that the original terms “pre-processor” and “post-processor” are way too confusing. Tools like Sass incorporate optimisation and authoring features. And depending on the way you configure your PostCSS pipeline you have also features of both categories included.

In the end, both tools are CSS processors. Helping you to get stuff done.

Choosing the right tool for your workflow is actually just a matter of taste.

The biggest strength of PostCSS is its modularity. Instead of being confronted with a huge, monolithic architecture you just add those features that you really need. It’s abstract syntax tree parsing is compared to none in terms of speed and flexibility. I also get the feeling that people tend to smaller and simpler stylesheets when writing PostCSS. And I welcome this trend to simplicity.

And when it comes to optimisation, there just is no other architecture. Nothing can beat a nicely configured PostCSS processing pipeline.

It has also a vibrant ecosystem of plugins and features which aid you through your quest. But as with any plugin oriented tool, this can be both blessing and curse. You keep your processing pipeline tidy and clean. But at the same time, you are confronted with loads and loads of plugins. Some of the might be of little quality, others aren’t. With the idea to be as close as possible to CSS, people might even create plugins that could break when future CSS syntax actually arrives.

Concerning this issue, Sass is very restrictive at what is being added to it’s syntax and what not.

This feature was rejected from Sass because it's not clear what are custom properties and what are standards-based. https://twitter.com/PostCSS/status/618512398098518016 ...

In this sense, Sass is actually very conservative. Extending CSS syntax is prone to confusion not at all future friendly.

I guess this is one of Sass’s strengths. The syntax is clear. Distinguishing between additional features and real CSS is the very foundation Sass has been build upon.

But Sass’s monolithic approach can be overwhelming at times. Most people already have a huge build setup. Adding a light-weight tool sometimes feels more comforting that dropping the heavy load of the Ruby original.

CSS Processors #

Sass and PostCSS are basically the same in terms of processing. “Pre-processors” and “post-processors” don’t exist. They are CSS processors, taking care of both authoring and optimisation features.

But they do take a radical different approach when it comes to architecture. Sass is a conservative, monolithic system clearly meant not to be CSS. For a multitude of valid and well-thought reasons. PostCSS is a light-weight and flexible architecture trying to be as close as possible to CSS. It allows for more simpler source files, and even intends to become obsolete at one point. When all the future syntax is there, you drop one plugin after another. The non-curated nature of its extensibility is also the biggest risk. When we can extend CSS syntax at will, does this have any influence on upcoming features and their native implementations? And if so, a good influence?

Whatever tool you add to your build process, as long as they help you writing good code, you can’t be wrong.

Huge thanks to Hugo Giraudel, Maxime Thirouin and Vincent De Oliveira for their insights and feedback! Maxime also wrote about that topic on his (French) blog.