From Medium: PostCSS misconceptions

This post was originally published on Medium in 2015. I decided to carry it over to my blog to keep it safe

You are not the only one, my friend.

A few days ago, the following quote popped up on my screen:

Five years on …this still doesn’t exist; this is still something that every single web designer/developer I know is crying out for. How do we make :parent happen?Polyfill? Post-CSS? A WC3 community group?

It’s Jeremy Keith rooting for the parent selector in CSS in a comment made in Remy Sharp’s blog. A feature developers have been awaiting for ages, but which seemingly will not to land in our browsers anytime soon. I nodded at the first suggestion made by Jeremy (a Polyfill), but questioned how the second one would even be possible to realise. PostCSS is a good way to optimise existing CSS code, but how can we add functionality in CSS by just modifying syntax?

With this question raised, Andrey’s talk from CSSConf now up and online on Youtube, and the A List Apart preprocessor panel discussion mentioning PostCSS and transpiling, I slowly realised the following: The idea of postprocessing finally has reached developers, but its scope is still a myth to some.

Misconception Number One: Performance #

The PostCSS Repository states:

Performance*:** PostCSS, written in JS, is 3 times faster than libsass, which is written in C++.*

Every time you hear something like this, ask yourself: based on what benchmark?

The PostCSS developers not only provide us with their findings, but also tell us how they got here. Take a good look at their preprocessors benchmark. They load a compiled Bootstrap file, which is good for checking how fast and efficient their syntax tree is created, and add about four to five lines of code representing various concepts like mixins, variables and nesting rules. The data is prepared and piped through various preprocessing alternatives. The results are impressive, but hardly comparable to a real world scenario. Let’s try a different approach: Rather than using a pre-compiled version of Bootstrap, let’s compile Bootstrap itself.

Compiling Bootstrap’s Sass version with libsass is easy, since it exists already. In lieu of a non-existent PostCSS Bootstrap, we create a similar, however reduced example: PostCSS should replace one variable, and import pre-compiled CSS files. You can find the complete test setup here, and the Gulpfile right below:

var gulp = require(‘gulp’)

var sass = require(‘gulp-sass’);

var postcss = require(‘gulp-postcss’);

var importCSS = require(‘postcss-import’)();

var variables = require(‘postcss-css-variables’)();

gulp.task(‘css’, function() {

return gulp.src(‘css/bootstrap.css’)

.pipe(postcss([importCSS, variables]))

.pipe(gulp.dest(‘postcss-output’));

});

gulp.task(‘sass’, function() {

return gulp.src(‘sass/bootstrap.scss’)

.pipe(sass())

.pipe(gulp.dest(‘sass-output’));

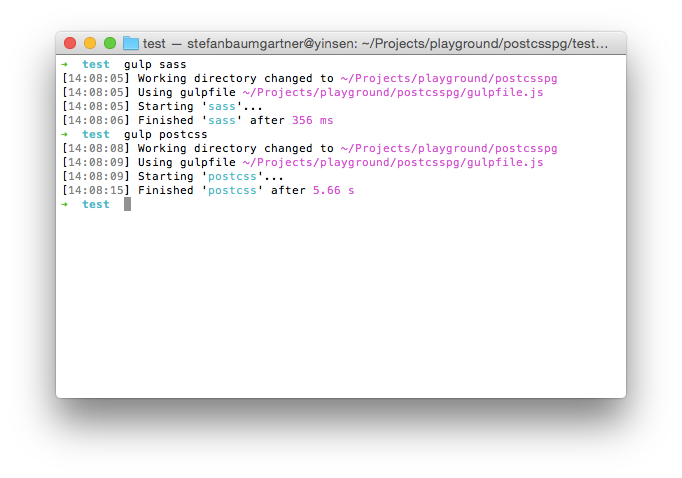

});Gulp’s Sass plugin based on libsass compiles Bootstrap in roughly 350 milliseconds. PostCSS, just importing files and replacing one variable takes more than 5 seconds. Note that there’s a huge jump when using the variables plugin (which might not be as good to begin with), but consider that we aren’t even close to including all the Sass features used by Bootstrap.

Comparison between PostCSS setup and Sass Setup, compiling Bootstrap

Comparison between PostCSS setup and Sass Setup, compiling Bootstrap

Benchmark results are always something to reconsider, as they’re most likely tailored to support one technology’s strengths and hide their weaknesses. Same goes for the example above: This setup was designed to have a positive outcome for Sass and a negative one for PostCSS. However, which one’s more likely to be more up the way how you work? You decide.

PostCSS faster than anything else. No. (Or: not necessarily).

Misconception Number Two: Future CSS syntax #

PostCSS, having the term “post processing” already in its name, is widely believed to be a CSS transpiler, compiling new CSS syntax to something browsers already understand:

Future CSS**:** PostCSS plugins can read and rebuild an entire document, meaning that they can provide new language features. For example, cssnext transpiles the latest W3C drafts to current CSS syntax.

The idea is being to CSS what Babel.js is to the next EcmaScript edition. Babel.js however has one advantage in fulfilling this task: JavaScript is a programming language. CSS is not. For every new functionality, Babel.js can create some workaround with features the language already provides. In CSS, this is close to an impossibility.

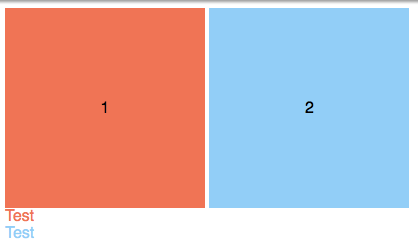

Take a simple example considering CSS custom properties (more widely known as CSS variables). We define our custom properties at the root element, like suggested, and reuse them throughout the document. However, we also want to create an alternative styling, just replacing the old variable with the new one:

<div class=”box”>1</div>

<div class=”box alt”>2</div>

<div class=”text”>Test</div>

<div class=”text alt”>Test</div>The CSS:

:root {

--main-color: tomato

}

.box {

background-color: var(--main-color);

}

.text {

color: var(--main-color);

}

.alt {

--main-color: lightskyblue;

}Custom properties already work in Firefox, so check out the example on Codepen.

Having custom properties available in the cascade shows the one true strength of this new specification, and definitely needs either a Polyfill or browser support. It’s not something we can just teach our browser by using it. This idea of using new CSS features that aren’t even implemented right now is not that new. You might remember Myth, stating the very same. My colleague Rodney Rehm de-mystified the idea of polyfilling in CSS in great detail in his article from 2013. Go read that, it’s not only highly recommended, but also known by all Future CSS tools you find out there.

Did you ever wonder why this new syntax of next generation CSS is so totally unfamiliar to the things we know from years of using preprocessors? Mainly because CSS’ syntax is meant to be used in an environment where it will also be executed: The browser. It relies on functionality and implementation details that cannot be recreated by simply processing it.

If we really want to use Future CSS today, which adds new functionality to its behaviour and is not only syntactic sugar, we need a solid browser implementation or good Polyfills. The guys at Bootstrap do something similar with the “Hover Media Query” shim they provide. It uses PostCSS to understand the syntax, but requires a JavaScript to add said functionality.

So, PostCSS for Future CSS? No. (Or again: not necessarily).

Misconception Number Three: Postprocessing #

It’s again in the name. PostCSS gears strongly towards postprocessing steps, meaning you write an already working CSS file, and enhance certain parts by running it through processing software. Unlike preprocessors, who take a different, non browser-compatible language and create CSS out of it. Concept-wise, they deal with different things:

Preprocessors are meant as authoring tool, to provide some comforts while producing CSS. The goal for them is to make editing and crafting CSS as convenient as possible.

Postprocessors on the other hand take an already complete and runnable CSS file and add additional information to optimise the output. Tasks include minification, concatenation and applying fallbacks. Things that are meant for automation.

When written down, you see that each of those concepts stands on its own and has little to no overlap with the other one. But when we look at the tools implementing those concepts, those areas are not black and white anymore.

CSS has a very easy syntax, one that can be interpreted by preprocessors like Sass or LESS. With the SCSS syntax being a strict superset of CSS, every CSS file becomes a valid Sass file. This means that as an author, you do not have to use any of Sass’ features like mixins, nesting or variables. Instead, you can just use Sass to bundle your styles into one file and minify it for optimised output. So Sass as a tool already includes postprocessing steps.

LESS, with its plugin architecture, can also run autoprefixing and advanced CSS minification as processing step, with it still being labelled as preprocessor.

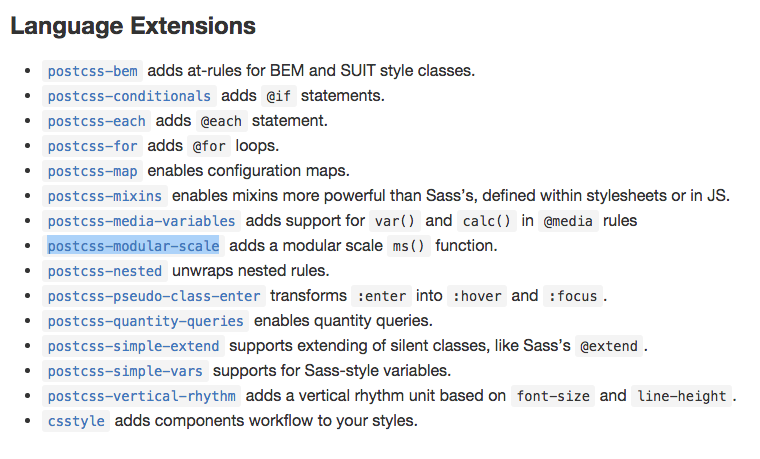

On the other hand, PostCSS has a wide variation of syntax extensions, some of them even providing Sass-like syntax and even at-Rules like “for”, “if” and sorts.

Language extensions that are clearly not part of the CSS specification. And most likely never even will be. So how does PostCSS differ now from a preprocessor? The answer is: It doesn’t. Not at all.

Does a PostCSS extension automatically add a postprocessing step? No. (You guessed it: Not necessarily).

The role of PostCSS in the greater scheme of things … or at least in mine. #

One might think that I’m a strong opposer of PostCSS, but I am not. Actually quite on the contrary. There’s one thing PostCSS does absolutely right: Providing an easy and flexible way to access the abstract syntax tree, for changing and modifying attributes. I wouldn’t want to work without tools like Autoprefixer anymore, and having a fast way to add pixel fallbacks or calculate a media query free stylesheet for legacy browsers is not only handy, but helpful and boosting productivity. There are a lot of things that should be done in postprocessing steps, and for those things I do use PostCSS.

As an authoring tool, however, I don’t like it so much. Using next generation CSS syntax like var and calc, and not being able to use them in their full scope is misleading. And for just using them in a reduced way the syntax is way too convoluted. Math and variables in Sass are easy, and for the moment, more powerful when you are in the process of creating.

Same goes for language extensions. Mixins in Sass are easy to use and follow a pattern that identifies them being from the Sass superset rather the original language alone. PostCSS, sticking to a parsable CSS syntax tree has some constraints there, thus additions like mixins or operators like for and if seem a little tacked on. Other additions, like having a clearfix hidden in a CSS property, blend a little too well with the surrounding real CSS to be spotted by people who might not be so familiar with your way of creating CSS. It might be outright considered … harmful (it isn’t, wink wink).

However, if you would ask me which tool I will be using a year from now, based on the ecosystem we have at the moment, it might actually be PostCSS. The days where we’ve overused Sass features are most likely over, at least for me, and for a lot of people writing in a preprocessor’s language doesn’t differ so much from writing real CSS. Optimising your stylesheets however is something we have to do. I would most likely do it with some selected single purpose software I can add to my existing build tool, for others the choice might be even more obvious:

Incomplete thought. You need a build step for CSS anyway (compression). So you might as well preprocess since it’s an easy ridealong. - @chriscoyer

Huge thanks to Betty Steger, Anselm Hannemann and Laura Gaetano for their feedback!